“Globelink” was a late-2010s proposal by the South Australian Liberal Party to modernise the state’s supply chain through targeted infrastructure investments. The ambitious program aimed to integrate road, rail and air freight services at a new intermodal freight super-hub at Monarto, 50km southeast of Adelaide, relieving urban road congestion and impacts on local communities. Several different projects were investigated, including new road freight routes into the city, a rail bypass of the Adelaide Hills, and even a second airport. The proposal drew widespread support from regional stakeholders for the development and employment opportunities it could bring, as well as from urban councils who saw the value in removing heavy freight from their communities.

To the dismay of many, the Globelink Scoping Study recommended that none of the Globelink proposals should proceed, as its economic analysis demonstrated that none would deliver a positive return on investment. According to the report, the rail option performed particularly poorly, notably claiming “the case for rail has deteriorated, with volumes even lower than previously forecast”. The Globelink Report thus became the latest in a long line of setbacks for proponents of an improved Adelaide Hills railway. But in a manner similar to earlier studies, its negative verdict was more a result of poor scoping than fundamental flaws in the concept. The study in fact provides substantial support to an Adelaide Hills railway upgrade – just not the Globelink version.

However, as Globelink continues to be widely cited as evidence against an Adelaide Hills railway upgrade, we feel it is necessary to address its shortcomings directly. We shall focus primarily on Globelink’s two rail-related options, as that is the main interest of this blog. We shall also be content to point out the strengths and weaknesses of the report, rather than to offer a wholesale correction – that matter has been adequately addressed between our earlier reviews of the Mainline Upgrade Report, the Interstate Network Audit and the Adelaide Rail Freight Movements Study (ARFMS).

Background

The Globelink policy was announced by then-opposition leader Steven Marshall on 28 January 2017 as a major infrastructure initiative. Despite industry skepticism, the Liberals made Globelink a high-profile promise for the 2018 South Australian state election. Though probably not a decisive factor in the Liberals’ success at that election, it proved a popular policy (especially in the Adelaide Hills and Murray regions), and resonated with the Liberals’ message of economic growth and infrastructure development after 16 years of Labor government.

After the Liberals comfortably won the election in March 2018, the business case was put to tender in June. KPMG was appointed the lead consultant by November, and the first two stages were completed a year later, by December 2019, costing a reported $2.4 million out of $20 million that had been allocated to the planned four-stage feasibility study. The Globelink report’s negative findings were quietly released on the Australia Day public holiday, Monday 27 January 2020, five years ago today. The Liberals declared their election promise fulfilled, and abandoned Globelink as a policy. Many constituents considered this a dereliction, having interpreted the promise as a commitment to produce actual infrastructure, rather than just yet another piece of expensive paperwork. Like previous reports of its kind, the detailed economic analysis was not included in the publicly released report, and its conclusions received little scrutiny.1

The Globelink rail bypass

Alignment

Globelink’s proposed rail alignment (left) is a variant of the Barossa Valley bypass route that has been kicking around since the early 1980s. It is similar to the ARFMS “Truro South” route (right), but differs in several significant respects:

- Its eastern junction departs from the existing railway at Monarto, instead of Murray Bridge – apparently a requirement to support the proposed location of the intermodal super-hub. This results in a somewhat longer alignment than the ARFMS (150km vs 144km).

- Between Gawler and Truro, it does not use the Kapunda Railway alignment – instead passing several kilometres further to the east, roughly following the Sturt Highway instead of the Thiele, avoiding Freeling and going much closer to Nuriootpa (possibly a result of faster design speed).

- The design speed is 160km/h, instead of 115km/h – this is a surprising specification, for which no justification is offered; the track would have no passenger utility, and fast freight has not been an industry goal for at least 25 years. Such a specification serves only to inflate construction costs, perhaps greatly so, by requiring a much straighter alignment through already very challenging terrain (it would double the minimum radius from 800m to 1,600m)

- Most crucially, the alignment is designed with clearances for single-stacked containers, rather than double-stacked. This is a truly baffling specification, putting the proposal at odds with the industry’s longstanding aspiration for full east-to-west double stacking on the Australian rail network, and more-or-less eliminating any operating cost benefit the new track might offer. There is likewise no explanation for this decision. I can only imagine it is an attempt to mitigate high capital costs, but then that is inconsistent with the overly high design speed.

The Reference Rail alignment is therefore a confusing choice. Aside from the strange mix of specifications (high speed but single stacked), there is no discussion about why this route option was selected in the first place, rather than the ARFMS “Southern Alignment” via Mount Bold, an upgrade of the existing railway, or any other possibility for that matter. There is some focus on the noise impacts of rail freight on nearby communities, perhaps suggesting an imperative to avoid urban areas, but this is not stated explicitly. It is not evident that the report has considered any other alignment options that might have delivered greater economic benefits. It seems the Truro route has been considered the de-facto preferred route since the ARFMS, despite there being no clear recommendation for such a conclusion in that report, or any since.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Even conceptually, a single-stacked Truro rail bypass really has very little going for it, and the economic analysis bears this out. The summary chart of the present value of costs and benefits over the 30-year study period is almost embarrassing – the results are so obviously bad that it tempts the reader to skim past it dismissively. But there’s actually a fair bit of insight in this chart if we give it a bit of attention. We’ll look at each benefit and disbenefit in turn; the study’s method is as per the Australian Transport and Planning guidelines (ATAP), assuming a base year of 2018-19, operations commencing 2025-26, and 30-year evaluation period at a 7% discount rate.2

- Residual Value ($166m) – this is the present value of the depreciated asset value at the end of the 30-year evaluation period; supposedly what the railway would be worth if sold, but more typically calculated simply as a decay function of capital costs. Indeed, we find that depreciating the capital cost of $4,743m by 2.5% annually for 30 years from 2026, and taking the present value in 2019 terms, comes to almost exactly $166m. It’s dubious whether this counts as a true economic benefit (it’s directly proportional to capital cost), and in any case, the fact that it is the *largest* benefit is somewhat absurd.

- Value of Time ($116m) – reflecting the value placed by freight customers on faster service, this is a reasonably good result, somewhat higher than Hot Rails estimated in our reevaluation of the ARFMS. This suggests a highly optimistic estimate of time saved over a longer alignment (and possibly explaining the selection of a 160km/h design speed)

- Environmental Externalities ($16m) – this benefit comprises mainly greenhouse gas and particulate pollution impacts, as well as noise and landscape impacts. It is substantially smaller than the Hot Rails estimate – unsurprisingly, as Globelink considered neither double stacking nor modal shift.

- Rail Freight Transport Cost Savings ($9m) – In any major infrastructure upgrade, you’d expect this benefit to be substantial. Instead, it’s insignificant. With reasonable estimates of future growth, the figure comes to something like $500,000 per year, or under $0.15/ton on 2018 volumes (that’s about a 0.5% saving for MEL-ADL freight, or 0.1% for MEL-PER). That’s nowhere near enough to make such a major capital investment worthwhile, nor to drive any modal shift away from trucks. But that’s not surprising with a single-stacked alignment (in fact it’s surprising that this line-item is even positive).

- Level Crossing Avoidance ($5m) – Another small amount, in line with the ARFMS estimates (and in the same ballpark as the Hot Rails estimate too). Note that this includes only time saved by cars and trucks waiting at level crossings, not the cost of level crossing collisions.

- Crash Costs ($-0.7m) – This one is interesting, not so much because it’s small (Hot Rails agrees it ought to be) but because it’s negative, ie, their model predicts an increase in road accident externalities. This indicates that the model is a simple rate per net-ton-km, and is unresponsive to both the population density and traffic interacting with the rail line, as well as the exposure score of any remaining level crossings. Hence, the slightly longer distance of the new line results in a slightly higher crash externality score, despite the new line bypassing most built-up areas and level crossings. It also confirms the lack of any modal shift from trucks, as any such shift would come with significant road safety benefits.

Below-rail operating costs

The study presents an implausibly high infrastructure operating cost, of $52 million per annum (about $350,000 per kilometre of track). This is about 40x higher than the ARTC average (or a third of the operating cost of their entire, 8,000km network), which demands some explanation that is not evident in the report. And furthermore, even if this figure were defensible, it should be relative to the base case. A brand new, modern track should have far lower operation and maintenance costs than the old, patched up Hills railway, and we would expect to see this reflected as a modest benefit, rather than a large cost.

A related claim made in the report is that the earlier ARFMS report (2010) did not include operating costs and therefore made the case too favourably; this is patently untrue, with that report making explicit and frequent reference to “below rail operating costs” (evident on many pages, but most obviously page 37, “Net operational efficiency benefits”), where it is clear that the ARFMS has considered the OpEx of both the existing and new alignment. Altogether, the Globelink report’s apparent misunderstanding of below-rail opex benefits does not inspire confidence.

Capital Costs

The economic analysis shows that the nominal $4,743m capital cost of the bypass discounts to a present value of $3,652m. At the discount rate of 7% and assuming the expense is evenly distributed over the years, this indicates a construction period of about 7 years (consistent with the base year being 2018-19 and start of operations in 2025-26).

Note that the headline CapEx figure of $4,743m includes $782m in design and contractor costs, and $1,355m in contingency (30% and 52% of direct construction costs, respectively, although it looks likely that contingency has been calculated as 40% of construction+design). These figures are at the high end of reasonable (see e.g. the DPTI’s Estimating Manual for Transport Infrastructure Projects), but at least they are explicitly defined.

Here’s where we need to be careful comparing between different proposals. The ARFMS (2010) estimated the Truro South route’s cost at $2.4bn in 2009 dollars, which accounting for inflation comes to $2.96bn in 2019 dollars. This figure included design, project management and land acquisition, but not contingency. Globelink’s figure on the other hand includes design and principals cost (comparable to project management) and contingency, but not land acquisition. Ignoring land acquisition as a small percentage (typically under 5%), the direct construction, design & project management costs of each proposal in 2019 dollars are:

- ARFMS “Truro South”: $2,960m

- Globelink “Reference Rail”: $3,388m

That puts the Globelink cost estimate about 15% higher than the ARFMS, possibly up to 20% if land acquisition were included. This seems a reasonable result, with any capital saving from the abandonment of double-stacking offset by the requirements of a faster design speed (and plausibly some cost escalation beyond CPI, given the ongoing surge of Australian construction costs).

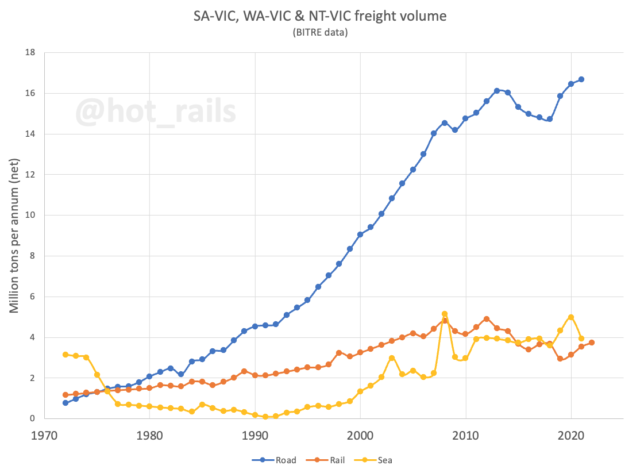

The core misconception: “demand has deteriorated”

Aside from the mis-specification of a longer, single-stacked route that could not possibly deliver any significant operating cost benefits, the Globelink study makes one other critical misconception. They note – correctly – that freight volumes on the railway have declined since the 2010 study. However, they conclude that therefore the potential benefits of a track upgrade have also declined.

This conclusion confuses actual market share for Total Addressable Market. Yes, rail volumes have declined, but not because of a reduction in contestable freight, rather because of the decreasing relative competitiveness of the railway. Globelink’s own numbers show a total SA-VIC freight market of 13.7mtpa3, with BITRE figures indicating the total addressable market – including road and sea freight – continues to grow in excess of 5% per annum! If an upgraded railway were to capture even a small percentage of that market (say, 5-15%, around the range anticipated in ARTC’s 2001 Interstate Network Audit) we would be talking about doubling the current volumes on the line, as well as taking a much higher share of future market growth. Furthermore, as this incremental market would be captured from trucks, rather than giving incremental improvement to freight already using rail, the economic benefit of each captured ton of freight would be high.

But of course, in order to capture any of this larger market, the railway must offer operational benefits over the current line – lower operating costs, faster transit, or higher reliability. The Globelink proposal fails to deliver this, and therefore its benefits are confined to just the existing customers. The report is therefore correct in its conclusion that the rail bypass as scoped would fail to return net economic benefits. But it’s erroneous to conclude that any rail bypass or upgrade would perform as poorly. In fact, another chapter of the Globelink report unwittingly makes the case for just such an upgrade. Let’s now take a closer look at Globelink’s least-publicised result: the “intermodal only” scenario.

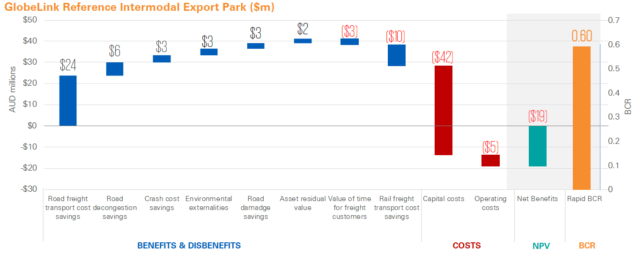

Globelink’s Intermodal Export Park

The second rail-related project proposed by Globelink was termed the Intermodal Export Park or “Reference Intermodal”, a minimalist plan to establish a new intermodal terminal east of Adelaide (either at Monarto or Tailem Bend), as well as on-dock rail at Outer Harbour. Containerised truck freight bound for Port Adelaide would then transfer to rail for the journey between Tailem Bend and Port Adelaide, utilising the existing railway, thus avoiding the congestion and delays associated with the road freight route through suburban Adelaide. While the report noted this would “require enabling policies from Government”, it fell short of advocating regulatory restrictions on B-Doubles using the South Eastern Freeway or metropolitan road network, thus limiting the likely modal shift from trucks.

Nevertheless, the economic evaluation of Reference Intermodal was fairly encouraging. While it was by far the most modest of the Globelink proposals, at a total capex of just $55m including soft costs and contingency, it also achieved by far the highest BCR4, at 0.6 (the next-highest BCR, at 0.2, was for the southern truck bypass route). The report does not provide figures for the volume of modal shift achieved, but we can use the economic analysis to make a reasonable estimate.

First, we see that the nominal $55m capital expense discounts to a $42m present value, confirming that the same 7-year construction period has been assumed before benefits begin (while reasonable for a multi-billion dollar bypass, this is an implausibly long lead-time for a small intermodal terminal, which could probably be built in a year or two). Retaining this timeframe assumption, as well as the study’s 2.1% annual growth rate for freight task, the present value of road freight transport cost savings ($24m) implies an annual saving of slightly under $2.5 million per year in the first year of operation (2025-26). Assuming a cost differential of $0.05/ntk5 (4c/ntk for rail vs 9c/ntk for road), there would be a saving of $6.30/ton over the 126km route between Tailem Bend and Outer Harbor. Therefore the total annual benefits would be achieved with a modal shift of about 390,000 net tons per annum from trucks to trains.

Crash costs can give us another indication of modeshift volumes. A $3m present value implies an annual benefit of $310,000 in 2025-26. Using the ATAP guideline values for crash costs of 0.05c/ntk for rail and 1.00c/ntk for road (based on Laird 2005), we come to a saving of $1.20/ton between Tailem Bend and Outer Harbour, and therefore a modeshift of 275,000 tons – a similar result to the previous method. Performing the same estimation using figures for environmental externalities and road damage also puts us in the same ballpark. We’ll take 300,000 net tons as a reasonably mid-range figure (roughly 30,000 twenty-foot equivalents per annum). That’s an increase to current rail freight volumes of about 6% – equivalent to around 2% of the total freight carried by trucks on the freeway, or 8% of the current container volume handled by Outer Harbour. Put another way, it’s 15,000 trucks off the road each year (or 40 per day). This is a fairly modest volume; it could be handled by four, perhaps five single-stacked container trains each week.

Case study: Wimmera Intermodal Freight Terminal

The Globelink study mentions western Victoria’s Wimmera Intermodal Freight Terminal, near Horsham, as a project analogous to its proposed Tailem Bend terminal. This facility opened in 2012 at a cost of $17.5m and was subsequently supported by a modeshift incentive scheme. This is a closely comparable project, both in its capital cost and throughput (recent figures claim 15,000 40-foot containers per annum, ie, 30,000 TEU). BITRE has some interesting further reading on this topic: Why short-haul intermodal terminals succeed.

If this is what is achievable just by putting an intermodal facility at Tailem Bend, then how much more freight could be captured if the railway were actually upgraded? Double-stacking and curvature improvements to the existing corridor could deliver operating cost benefits and time savings far greater than the much longer Truro bypass, at much lower capital expense. Additionally, or alternatively, market incentives for rail customers (or disincentives for road) could be offered to drive greater modal shift. Unfortunately, the Globelink study does not explore any of those possibilities, confining their sensitivity tests to comparatively uninteresting scenarios like lower or higher CapEx, or alternate terminal sites. It does however strongly suggest, as Hot Rails has been arguing all along, that an intermodal terminal plus an upgraded existing track (rather than an entirely new track) would deliver large volumes of modal shift and result in high economic benefits.

Aside – higher rail freight costs?

One other aspect of the Reference Intermodal benefits chart caught my eye. Rail Freight Transport Cost Savings are estimated at negative $10 million over the study period. The explanation for this unexpected result is that: “Shifting freight from road to rail will result in an increase in rail transport costs as a new rail service would need to be provided.” This is the same mistake made with respect to the operating costs of the rail bypass – those costs should be relative to the base case. Here, the cost of additional rail services should already be fully accounted for in road transport cost savings. Removing this $10m disbenefit would increase the project BCR from 0.60 to 0.84, which is fairly close to the point of economic viability (and could plausibly be pushed beyond it with further economic incentives, or even merely assuming a more reasonable construction period).

Or perhaps we are to conclude that the “road savings” figure actually refers to the full cost of truck trips foregone, and “rail savings” therefore correctly refers to the full cost of additional rail trips? In this case the implied modal shift would drop to 208,000 tons per annum, but conversely the implied benefit per ton of freight carried for crash costs, externalities and road damage becomes implausibly high. I’m inclined to put this down to erroneously double-counting the costs, especially since we know that the same mistake has been made elsewhere in the report.

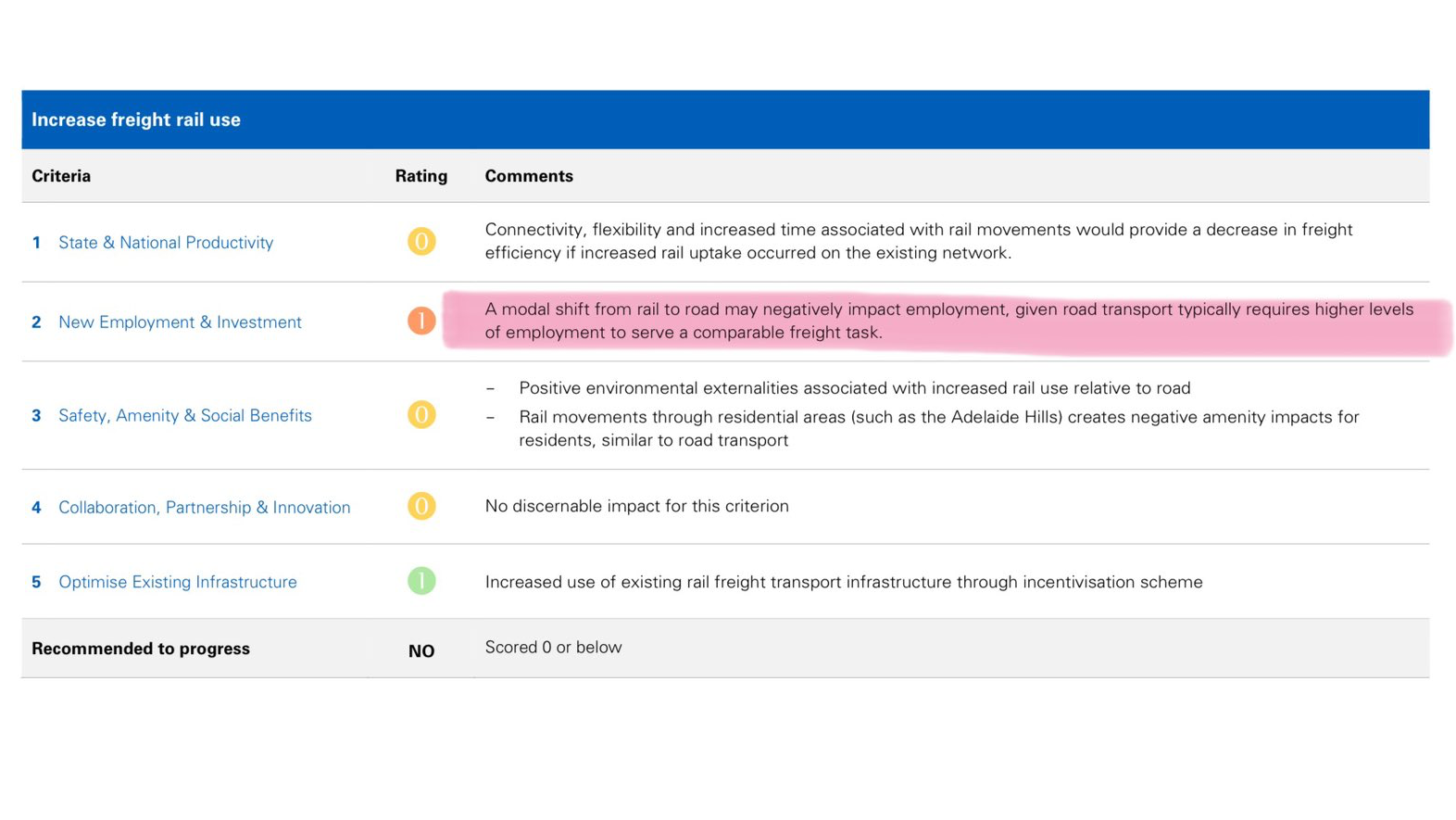

Longlist Options Refinement

So why didn’t Globelink look at any of those other track upgrading options, or mode shift incentive schemes for that matter? As it turns out, they did, albeit briefly. There’s more to the Globelink report than just the 5 headline projects that progressed to full economic analysis – they started out with a long list of 60 potential projects covering a variety of capital and regulatory approaches. Most of these were rejected via a two-stage screening process – Stage 1 was a “strategic fit and viability assessment” that determined whether to progress to the Stage 2 shortlist. 20 options progressed to the stage 2 review, which involved a “multi-criteria analysis” or MCA, also known as a “selection matrix”, where each option is assessed and scored against several criteria.

The full details are in the appendices, often where the most interesting parts of a report are found – and Globelink does not disappoint in this respect. We won’t go into detail on every one of these, though noting several instances of poor selection criteria resulting in absurd outcomes (e.g. several proposals to improve rail freight are eliminated based on the fact that they might result in reduced employment for truck drivers – AKA exactly what such a scheme is intended to achieve – or the circular argument that Mount Barker has low public transport usage, therefore improved public transport would not be used!).

However, there’s one project that didn’t make the cut, yet stands out so obviously as deserving serious consideration, that it’s worthwhile for Hot Rails to take a deeper dive.

Double Stacking

“Tottenham to Keswick double stacking upgrades” was one of the longlist options excluded at Stage 1, the strategic fit analysis. This is a project that’s on the National Infrastructure Priority list – what could be the strategic misalignment with Globelink’s goals? The project has two disadvantages listed – first, that the ARTC has advised current volumes on the line are insufficient to justify investment (which would be a financial, rather than a strategic objection), and second, that it would require investment from the Victorian government (which I suppose could be seen as strategic, but really just means intergovernmental collaboration would be needed – hardly a show-stopping issue).

But more interesting is the list of advantages – firstly, efficiency improvements due to eliminating restacking delays at Dry Creek (which would be significant!), but the second advantage is worth quoting in full:

Double-stacked trains could potentially produce savings of up to 25 per cent for rail customers

Stop right there – reducing operating costs by 25% is an enormous benefit. Depending on your assumptions, that’s something like $33 million per year for just the existing rail customers (4mtpa x 828km x $0.04/ntk x 25%), which equates to a present-value benefit of about $320 million over the study period. That’s larger by far than any single benefit identified in the entire study (the next largest is $129m for the stupendously expensive Cross Road Tunnel option). There would also be additional benefits, including Value of Time (through elimination of restacking delays), and residual asset value, but most notably modal shift from trucks. To a first-order approximation, a 25% cost saving ought to induce about 9% of truck freight to switch modes (25% x 0.35 road-rail cross-elasticity of demand, per BITRE’s Transport Elasticities Database), which would be 1.23mtpa. Assuming operating cost savings of $0.05/ntk, externality savings of $0.03/ntk (again based on Laird 2005), and an average distance of, say, 500km (roughly Adelaide-Stawell), that’s $49.2 million per annum, and a present value of $472 million over the study period. Add in modal capture from coastal shipping, time savings and other benefits, and we’re definitely well over $1b in benefits.

Would that be enough to exceed project costs? While Globelink does not estimate a capital cost for Tottenham to Keswick double stacking, the 2010 Adelaide Rail Freight Movements Study did – $700m in 2009 dollars, excluding contingency.6 If we escalate that cost by the same proportion as Globelink did for the Truro South route, we arrive at about $1.38bn in 2019 dollars, including contingency. This figure is somewhat debatable – some major elements of the project have already been completed (notably Goodwood and Torrens Junctions, at a cost of almost $350m), but conversely it excludes works on the Victorian side (mostly minor clearance works, and also the difficult Bunbury St Tunnel in inner Melbourne). But let’s take it as a reasonable estimate – keeping the same assumption of a 7-year construction period (which we also did when estimating the benefits above), that discounts to a present-value cost of $1,063m, almost certainly resulting in a BCR greater than 1.

Upgrading the existing line to double stacking clearances would therefore very likely have been the standout project of the Globelink study. Its exclusion speaks to the false scientism of the method – attempting to analyse component projects in isolation loses sight of the broader benefits to the whole network. We’ve seen this time and again with successive analyses of the Adelaide Hills Railway that treat it as a minor project of local or at best regional importance, when it is in fact a project of national significance, a strategic bottleneck impacting freight from every state and forcing more trucks onto the roads – the costs of which are ultimately borne by local communities around Australia, capital and regional alike.

Conclusion

Globelink presents a negative verdict on an Adelaide Hills railway upgrade, but that conclusion is not supported by its own numbers, which suggest significant modal shift would be achieved with very modest improvements to rail infrastructure. Like its predecessors, a correct analysis actually shows this would deliver significant economic benefits. The ongoing failure to target this low-hanging fruit is now imposing very real costs on the Australian economy. As long as they keep publishing business cases for Adelaide Hills rail that are so manifestly inadequate, I will keep publishing rebuttals to them.

Astonishingly (though perhaps unsurprisingly), road bypass solutions are still being pushed, despite scoring as even worse than the rail options in Globelink’s analysis. The proponents seem to have settled on a B-Triple bypass of the Adelaide Hills broadly following the same route as the proposed railway via Truro – termed the “Greater Adelaide Freight Bypass” – which Globelink dismissed due to vanishingly small benefits. There will much more to say on that when the business case – apparently already complete – is released sometime later this year.

- The Globelink report can be found at the Wayback Machine, here, or alternatively archived on the website of Our Roads SA, an advocacy group opposed to the expansion of Cross Road as a B-Double route. ↩︎

- All costs in 2019 Australian Dollars, except where otherwise indicated ↩︎

- Million tons per annum ↩︎

- Benefit/Cost Ratio – a value of 1 or more indicates greater benefits than costs over the life of the project ↩︎

- Net-ton kilometre – a metric ton of freight payload (excluding containers etc) carried for 1km ↩︎

- Earlier estimates include $231m (van Geldersman & Leviny 2005, 2003 prices) and $120m (Interstate Network Audit 2001, based on a 1995 estimate by Ove Arup) – $337m and $193m, respectively, in 2019 dollars. Both these estimates were for modifying existing structures only and did not include grade separations or other track upgrades that later estimates included. ↩︎

One minor nitpick – the constraint on double stabling into the middle of Melbourne is the Bunbury Street Tunnel, not Montague Street.

Good pickup, have fixed it. Mixing up my troublesome freight structures lol.