Last week, the Spanish train manufacturer Talgo made an unexpected entry into the high-speed rail debate in Australia, claiming that state-of-the-art tilting trains travelling at speeds of up to 200km/h could cut the journey time from Sydney to Canberra in half, from over four hours to “about two hours” (Two-hour train ride between Canberra and Sydney on the cards, Canberra Times, 5 April 2017), although a later article suggested two and a half. Talgo claim that this could be achieved with “little to no modification” of the existing rail infrastructure, at a cost of under $100 million, and be underway within 12 months.

The public reaction was skepticism bordering on frustration – yet another high-speed rail proposal, yawn. However, the Talgo proposal is genuinely different to what we’ve seen in recent years from AECOM, Beyond Zero, CLARA or HyperloopOne. Rather than pie-in-the-sky fantasies costing hundreds of billions or dollars and taking decades to build, Talgo’s proposal is more affordable by a factor of a thousand, and would be ready sooner by a factor of at least 10. In short, the plan passes the most basic sanity test of achievability – it’s something that a state premier could champion, and have it ready and operational well in advance of the next election.

This is the kind of approach favoured by Hot Rails – moderate top speeds in order to maximise use of existing infrastructure (and minimise cost), and near-term construction timelines to optimise financial return and political motivation. The proposal is more modest than that espoused by Hot Rails (2 – 2.5 hour travel time vs. 91 minutes) but a far lower cost ($100 million vs $4.8 billion). It’s hard to argue with a cost-benefit ratio like that! But is the proposal realistic?

The Talgo Proposal

Talgo XXI diesel tilting train. Image: Talgo

Let’s start with the cost and what that tells us. $100 million is almost absurdly cheap – barely enough to pay for two eight-car trainsets. If the whole of the $100 million was for rollingstock, that would make about $6.25 million per railcar (substantially cheaper than the Queensland Rail Tilt Train at $8m per car). We can therefore reasonably conclude that Talgo plans no upgrade at all to the track, signaling or stations, and no electrification.

No electrification means Talgo is almost certainly proposing to use the Talgo XXI diesel tilting train. Developed back in 2002, it’s still an impressive bit of kit, claiming the world record for a diesel powered train at 256km/h. It’s rated for 220km/h in operational use, which is easily fast enough to achieve HotRails-like performance. But how does it go in the curves?

The XXI is a passively tilting train, meaning that it tilts naturally using the inertial forces as the train travels around a curve. Talgo claim that this is technology is “state-of-the-art”, but it is actually at the low end of the performance spectrum for tilting trains. Its performance would be lower than an equivalent “actively tilting” train that uses hydraulic or other mechanical means to actively lean into a turn. We can therefore expect modest speed improvements on curved track in comparison to active-tilting rollingstock such as the Italian Pendolino or the German ICE-TD.

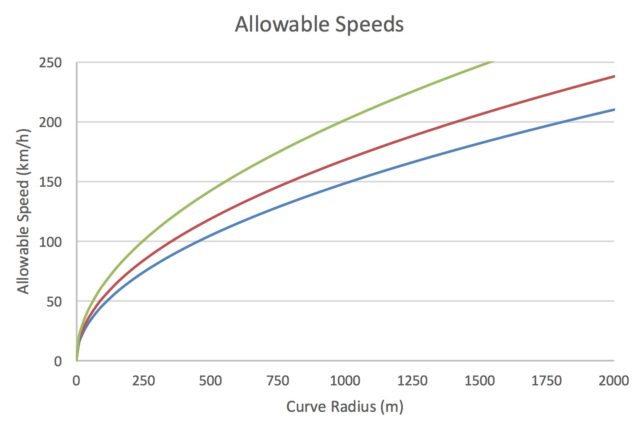

Talgo’s technical specifications bear this out – the XXI is rated to 9 inches of cant deficiency (225mm), which is at the low end of typical tilting train performance – the following chart shows how the XXI would stack up (the green line shows the maximum performance of active-tilting trains, red shows the Talgo, and blue shows the existing XPT service in NSW):

It’s evident that the XXI would most probably offer a modest increase in speed through curves compared to our existing XPT – but only between 12 and 15%. The practical limit of tilting train technology increases this to about 35%, however to achieve this would not only require active tilting technology, but also a substantial modification of the track to increase the bank angle of the track itself. Not only is this expensive, but it also makes the track unsuitable for freight use – not something we want to do any time soon.

The existing track

The existing Canberra-Sydney railway is 330km long and takes a scheduled 4:06 hours; to do it in 2 hours would require an average speed of 165km/h, which sounds plausible enough with a machine capable of 220km/h. However, two things conspire to make this a very difficult target to achieve – first, the curvature and transitions of the existing track, and secondly the congestion of large sections of the track, especially within Sydney.

Radius of curvature on the Sydney-Canberra line varies from about 300-400m through Macarthur and the Southern Highlands, to 1500m+ around Goulburn, down to as low as 200m through the Molonglo Gorge on approach to Canberra. Putting it all together, an optimistic estimate for the total time taken would be a bit over two and a half hours (excluding stops).

This means that even Talgo’s slower estimate of 2.5 hours (150 minutes) is highly optimistic. Adding operational limitations would push this out substantially. The existing track within metropolitan Sydney is highly congested, and it is unlikely that the Talgo would be any faster than the existing XPT in this section. The XPT is scheduled at 59 minutes from Central to Campbelltown, 21 minutes longer than in our table above. Add in half a dozen stops (the existing service does 9) at, say, 3 minutes time penalty per stop (two minutes decelerating/accelerating and 1 minute loiter at the station) and we’re nicely over 3 hours.

Tight curvature isn’t the only problem with the existing track. It also has poor transitions (that is, the gradual change in curvature between a straight section and a curve, or from one curve direction to another). While always important for passenger comfort, it is especially so for tilting trains as the train requires several seconds to tilt from one side to the other. This however is hard to quantify without a much more detailed look at the corridor, so we’ll ignore it for now.

Cost-benefit analysis

In short, two hours is probably not possible without major upgrades to the existing track. 2.5 hours might be possible for express services, but it’s probably going to be three hours or slightly more for a typical journey, compared to over 4 hours for the current service. Not really the kind of thing that will make headlines, at least against the 500km/h, magnetic levitating whizbang get-you-there-in-three-minutes napkin plans we’ve grown used to in recent years. So does this mean it’s not worth the bother?

On the contrary, if the Sydney-Canberra train service can be improved to 3 hours for under $100 million, that’s both incredibly good value, and a very significant performance milestone. On a cost-per-minute-saved basis, the cost is about $1.7 million per minute saved, far better value than the Hot Rails proposal at $31m/min, or the AECOM proposal at $126m/min. And making the train even slightly faster than cars and coaches has tremendously significant implications for passenger demand.

Passenger demand

To be honest, there’s not much reason to take the train at the moment. Although the train fare is competitive, the travel time is not. The Hume Highway takes almost exactly 3 hours on a good day, and even on a bad day is rarely over 4 hours. The plane takes just an hour gate-to-gate, and even after considering CBD transfer at both ends, parking, check-in, security and all the other rigmarole it wouldn’t be much more than 2.5 hours. Embarrasingly, even the bus is faster. It’s no wonder passenger numbers on the train are dismal – it’s slowest by miles.

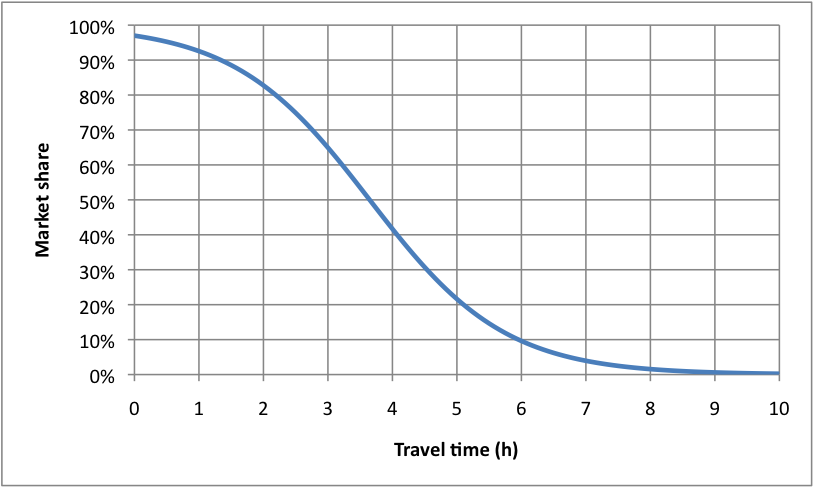

That’s why 3 hours is such a significant goal: it’s right on the transition where rail starts to become highly competitive with air travel, and with road vehicles. Once the train is as fast or faster than the Hume Highway, the potential travel market is enormous.

Currently, the 4.5hr rail service attracts a paltry 86,000 passengers per year – only a couple of hundred per day. It’s barely a rounding error in the total travel market between Sydney and Canberra. In a previous post, Hot rails calculated this market as comprising:

- Air: 950,000 per year (BITRE, 2016).

- Coach: 450,000 (plus another million or so to intermediate destinations)

- Commuter rail: 1,050,000 (from Sydney to the Southern Highlands and Goulburn)

- Car: 17 million per year, comprising:

- 5 million Sydney-Canberra

- 3 million Intermediate-Canberra

- 9 million Intermediate-Sydney

That’s almost 20 million passengers per year. Obviously a medium-speed railway will only capture a small percentage of this, but we can make reasonable estimates of how much. We could expect perhaps 50% of the air passengers to switch to rail given a travel time of 3hrs CBD to CBD (according to the travel time model developed by Peter Jorittma, shown above), most of the coach travel (let’s say 75%), and all of the commuter rail (the new service would presumably supplant the old). The percentage of modeshare gained from cars is most uncertain, but even if just 5% were to switch, that’s 250,000 trips CBD-CBD, and another 600,000 between intermediate destinations.

So that’s a probable ridership of 2.2 million passengers per year between CBDs, plus another 1.4 million to intermediate destinations, for a total ridership of 3.6 million passengers per year. If we set the typical fare at the same level as the existing rail service ($50 SYD-CBR), the railway could earn a farebox revenue of $145 million each year.

Timetabling

3.6 million passengers per year is 9,860 per day, or 4,930 in each direction. Looking at just the Sydney-Canberra leg, it’s 6,030 per day (3,015 in each direction – let’s call it 3,000). How many trains to we need to make that happen?

Well two trainsets sure ain’t gonna cut it. With a three hour travel time plus an hour for turnaround, that limits you to perhaps 5 trains per day in each direction (eg, departing at 6am, 10am, 2pm, 6pm and 10pm), and at 200 people per 8-car trainset (Talgo’s estimate) that’s barely 1,000 people per day. We’d need at least 3 times as many trains to meet demand; at a typical capacity factor of 75% it would be even more.

If our goal is 3,000 people each way per day, and assuming 200 people per train, that means we need 15 trains in each direction, each day. This could be achieved by eight 8-car trainsets, departing each station hourly from 5am to 8pm (yes, that’s 16 trains per day, but keeping it a multiple of 4 makes the scheduling easier). The first service of the day would arrive at its destination at 8am (sensible time for business travellers), while the final train would get in at 11pm (also not too barbaric a time).

Each train having a full hour’s headway means that passing loops should not be needed. The single-track section between Goulburn and Canberra takes almost exactly one hour with the XXI, so passing trains can do so at Goulburn Station. Train frequency will be limited to one per hour in each direction until the Canberra section of track is duplicated.

Also note that the above timetable is for eight, 8-car trainsets, a total of 64 railcars. This would obviously cost far in excess of $100 million, probably more like $400-500 million. However we would still be talking about a gross return on investment in the order of 30-35%, which should be highly attractive to the private sector.

Conclusion

Talgo’s proposal is sound, despite their goal speed most probably being overstated. Introducing a 3-hour Canberra-Sydney service doesn’t sound like anything revolutionary, but it would completely change the transport mix between the two cities. By making the train even slightly faster than cars or coaches, and comparable to the plane, it would immediately become a rational choice for the almost 20 million travellers between these two cities each year. And with Talgo offering to perform a trial run at no cost to the NSW government, there’s really nothing to lose.

Rather than an outdated curiosity that most Canberrans and Sydneysiders don’t even know exists, it would become a major player in the transport mix. Once so-established, consumer demand and planning necessity would drive an incremenal improvement of the track, eventually allowing much faster travel times, even as low as the 90 minutes proposed by this blog.

While this eventual goal would cost billions, upgraded rollingstock and improved timetabling would be an affordable and effective first step. The proposed cost isn’t especially more than you’d need to replace the existing rollingstock anyway. The trains running the regional routes are already very old – the Xplorer trainsets were introduced in 1993, the XPT way back in 1982. In fact, the XPT fleet is already in the process of being replaced, with bids expected by early next year.

Come to think of it, maybe that’s precisely what Talgo are getting at with this whole proposal 😉

Header image courtesy of Flickr/carris15

“And with Talgo offering to perform a trial run at no cost to the NSW government, there’s really nothing to lose”

Surley this is a no brainer, let the trial happen.

What have you got to lose Gladys and John Barilaro.