The named passenger train is a phenomenon that is curiously unique in the transportation world. For road transport, many of the great highways still bear glamorous names, but not generally the journeys made on them. Earlier, in the age of ocean liners, it was the vessels themselves that bore the famous names, so those names died with the ships, even before the whole industry was superseded by air travel. Aviation for its part never really embraced the tradition of naming individual aircraft, or the routes they flew. Only rail, with its interchangeable modular vehicles and long-lived fixed infrastructure, has given rise to the immortal named journey.

There have been thousands of named passenger trains since the growth of railways in the mid 19th century. Those names which have proved most enduring are typically attached to equally great trains – those that link great cities, serve a unique market, or have a storied history. Here I’ve made a list of the ten oldest named trains still running today; all have an operational lineage dating back well over a century and have a unique story to tell.

If I’ve missed one that should be here, or you have a favourite named train that you’d like to share, please let me know in the comments!

10 – Bernina Express

The Bernina Express is a metre-gauge sightseeing train connecting Chur, Switzerland, with Tirano, Italy, via the Bernina Pass (which gives the train its name), at 2,253m above sea level. Notably, it is the highest rail crossing in Europe, and the only rail crossing of the Alps not to have a tunnel at the pass. It takes 4 hours and 17 minutes to traverse the 144km route (making an average of 34km/h), with extensive tight curvature and steep grades up to 7%. The tourism-focussed service runs dedicated rolling stock with panoramic windows, and is timetabled once-daily (return) in winter and twice-daily in summer. Hourly local trains also run along the same route, year-round.

The UNESCO World Heritage route comprises two separate railways – the Albula Line (Chur to St. Moritz, built 1898-1904) and the Bernina Line (St. Moritz to Tirano, 1908-1910), with the Bernina Express starting service from 1910. The expense of their construction was justified politically by the disenclavement of the 20 remote alpine towns through which they passed, but both railways were additionally conceived explicitly as sightseeing experiences. For many, riding the Bernina is as much about the architecture as it is the natural beauty of the Swiss Alps; the route was built such that many of the spectacular stone viaducts and bridges could be seen from the train itself. The most famous of these are probably the Landwasser Viaduct and the Brusio Spiral, but there is an abundance of beautiful infrastructure to appreciate, with a total of 196 bridges and 55 tunnels on the route.

9 – Cornish Riviera Express

Since 1904, the Cornish Riviera Express has been the name given to the late-morning train between London Paddington and Penzance, Cornwall. Named for southern England’s beautiful coastline, upon its introduction it was noted as making the world’s longest daily non-stop run (the 396km from Paddington to its first stop, Plymouth).

After the introduction of HSTs in 1986, the fastest timetabled journey over the 526 kilometres to Penzance has been a shade under 5 hours (105km/h average). In 2018, HSTs were replaced by the Hitachi Class 802 (the bi-mode variant of the Class 801 Azuma); their higher speed allowed the same 5-hour schedule to be maintained, but with the addition of four more intermediate stops.

A number of comparable named trains also operate on the London-Penzance route. The Cornishman first ran in 1890, and though the name is still applied to the mid-afternoon service, it has a broken operational history and can no longer be said to be the same train it once was. Similarly, the Night Riviera is the second-oldest sleeper service in Britain, having been introduced in 1877. However it only received its current name in 1983, and thus is hardly an example of a notably long-lived name.

8 – Ocean

ViaRail’s Ocean, formerly the Ocean Limited until 1966, currently runs three times a week in each direction between Montreal, Quebec, and Halifax, Nova Scotia; the name is a nod to the maritime culture of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia through which the train passes. It originated as a limited-stops summer special in 1904, although its predecessor and companion train the Maritime Express was inaugurated six years earlier, in 1898. The Ocean takes almost 22 hours to run the 1,346 kilometre route (an average of 61km/h).

In 1955, the Ocean became the flagship train of Maritime Canada, as the frequently-stopping Maritime Express was losing patronage due to the Ocean’s faster travel time. Commensurate with this enhanced status, Ocean was outfitted with new Budd “Château series” stainless steel rolling stock, including the iconic Skyline and Park Series observation dome cars. This stock is predominantly still in use today, though sadly without the streamlined “Park” end coaches, because the recent removal of turnaround facilities at the Halifax terminal now necessitate a push-pull configuration with locomotives at each end.

7 – Sunset Limited

The Sunset Limited is billed as the oldest continuously operating named train in North America, having been introduced by the Southern Pacific Railroad in more-or-less its current form in 1894. Taking its name from the spectacular evening colours of the desert landscape through which it passes, the 3,211-kilometre, 45-hour journey starts in Los Angeles and follows the southern border region of the United States, making 20 stops throughout California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and Louisiana, before terminating in New Orleans. The present timetable offers three return journeys each week. Upon introduction it was America’s second transcontinental route, with the significant advantage over its northern competitor of not having to contend with seasonal snows of the high Rocky Mountain passes.

Between 1993 and 2005, the Sunset ran the only truly transcontinental train in North American history (ie, a direct run from the Pacific to Atlantic coasts without a change of train), continuing through Mississippi, Alabama and Florida to terminate in Orlando (even going as far as Miami until 1996). This extended route covered 4,450km in just over 67 hours. Sadly, in 2005 Hurricane Katrina washed out the line east of New Orleans, and (incredibly) it was not rebuilt to modern passenger standards due to a lack of funding. Since 2016, there have been several proposals to reintroduce service east of New Orleans, but as of 2022 none have yet come to fruition.

6 – Crescent

Amtrak’s Crescent, which runs between New York and New Orleans, is named after its southern terminus, which bears the moniker “The Crescent City” due to the shape of a bend in the Mississippi River on which its French Quarter stands. It makes the 2,216km run daily in each direction, making 33 stops and taking a scheduled 31.5 hours (70.3km/h).

The earliest direct ancestor of the Crescent was the Washington & Southwestern Vestibule between Washington DC and Atlanta, introduced in 1891. By 1906, it had been extended north and south to its present termini and renamed the New York & New Orleans Limited; it was renamed the Crescent Limited in 1925, shortened to simply Crescent by 1938. So while its name may be younger, the service itself is some three years older than the Sunset Limited.

Amtrak is reportedly considering cutting its long-distance routes, aiming instead to compete directly with airlines on shorter routes. This is despite objectively strong ridership – the Crescent carried 295,000 passengers in 2019, or about 400 per train. It’s hard to make a direct comparison with air travel due to the variety of potential city-pairs served, but that sounds like a pretty good market share for a train that averages just 70km/h with once-per-day service – probably in the 5% range. It would be a shame if this historic train fell victim to misguided economic “rationalism”, rather than being upgraded to meet the needs of modern travellers. We shall see.

5 – Punjab Mail

There is something gloriously unruly about the Indian Railways. Animals and pedestrians wander the tracks freely, and limbs protrude from overcrowded open-air second-class cars to catch a cooling breeze. Despite this, the network has one of the highest levels of service in the world – the passenger network is the world’s third largest after China and Russia, and has by far the highest ridership in terms of passenger-kilometres. It also has one of the highest proportions of electrified track – 84% – which is especially impressive given the size of the network. It is possible to travel to practically any major Indian town entirely by train – something no country of comparable size can claim.

There are a great many named trains in India, but the Punjab Mail is the oldest that has operated continuously and held its current name for most of that time. It originated in 1889 as the Bombay Mail between Bombay (now Mumbai) and Delhi. It received its current name in 1905 when it was extended to Peshawar in modern Pakistan. After partition in 1947, it was foreshortened to the border town of Firozpur. It makes a daily run in both directions, covering the 1,930-kilometre route in 34 hours, making 56 stops. As the average speed is above 50km/h, it qualifies as “superfast” (!) and the fares are therefore subject to a surcharge; a first class (air conditioned) ticket costs ₹4,960 (US$60), a standard sleeper ₹770 ($9.30), and second class sitting ₹470 ($5.70) – pretty good value for an almost 2,000km journey!

4 – Sud Express

The Sud Express (Spanish: Surexpreso, Portuguese: Sud Expresso) is the longest-lived night train in Europe, having linked France and Portugal since October 1887. Originally running from Paris to Lisbon via San Sebastián and Madrid, and operated by Wagons-Lits (the same company that ran its more famous cousin, the Orient Express), the service was truncated to Hendaye on the French border in 1989 upon the opening of the Atlantic TGV. As of 2019, the 1,066km route was scheduled at just over 12 hours, running daily in each direction and making intermediate stops at San Sebastián, Coimbra, Entroncamento and Lisbon East. Archived photos from Seat61.com reveal a modern and comfortable fitout comprising sleepers, 6-seater couchettes and luxury recliners.

The COVID lockdowns forced the discontinuance of the Sud Express in early 2020, and at time of writing it is still suspended. Despite being upgraded to refurbished Talgo-IV rolling stock relatively recently in 2010, the contract with Renfe for the Talgo stock was allowed to lapse, and the carriages were returned to Spain. Although Portuguese Railways acquired much of the pre-2010 Sud Express rolling stock in 2020 (pictured above), there are presently no concrete plans to reintroduce night trains to the Iberian peninsula. However, the planned 2023 completion of the Basque-Y high speed line raises the exciting possibility of a direct standard-gauge, high-speed service between Paris and Madrid, possibly continuing again to Lisbon when the Portugal-Spain high-speed line is completed (currently planned for 2030). Don’t consign the Sud Express to history just yet.

NOTE – Another Wagons-Lits train, the Nord Express, first ran a few years earlier in 1884 between Paris and St. Petersburg, but was discontinued after the end of World War II and the advent of the Iron Curtain. In 1951 the name was reintroduced for the night train between Paris and Copenhagen, and since 2007, Paris and Hamburg. Although still bearing the name of the original train, the modern service has been foreshortened to such a degree that it is no longer the same service at all. For all intents and purposes, the Nord Express ceased to exist in 1939.

3 – The Overland

Number three on the list, and the only train from the southern hemisphere to make the cut, is The Overland, which has connected Adelaide and Melbourne since January 1887. Although not officially named until 1926, contemporary newspaper reports show that it was popularly dubbed The Overland from its earliest days (it was then a fairly common moniker for long-distance rail routes). The name draws a distinction with the main competitive mode of the time – ocean liners – which were, until the railways, the only alternative to the slow and often dangerous “overland” route by horse and cart. The decision to formalise this somewhat-generic name is most likely an homage to the legendary Overland Limited between San Francisco and Chicago, perhaps most clearly evidenced by the adoption of the Southern Pacific Railroad’s “winged wheel” motif on the South Australian Railways 500-class “Mountain” engines in 1936. It was a time when Australian railways were rapidly modernising after decades of sub-standard service, and the state-based rail agencies were keen to emulate the great railway lines of the world.

The only named Australian trains to pre-date The Overland are the various discontinued predecessors of the Sydney-Melbourne XPT, which has been sadly nameless since 1993. Victoria’s Northeast Railway Line reached Wodonga in 1873, while NSW’s Main Southern Railway reached Albury, on the opposite bank of the Murray River, in 1881. Australia’s first named train, the Sydney Express, began in 1883 when the Albury-Wodonga Railway Bridge was completed, yet it still required a break-of-gauge at Albury. From 1937, the Victorian leg was rebranded as the Spirit of Progress; the NSW leg was changed to the Riverina Express in 1949. Upon gauge standardisation in 1962, both trains were extended to Melbourne and Sydney respectively, with the NSW-based leg rebranded Southern Aurora. In 1986, the two trains were merged into a single service, branded the Sydney/Melbourne Express, which in 1993 became, simply and unimaginatively, the Sydney-Melbourne XPT.

2 – Orient Express

I debated whether or not this list should include the most famous train in the world; the purists will tell you that the “real” orient express was discontinued in 2009, and that the glamorous train featured in Agatha Christie’s murder mystery is a different train altogether (the Venice-Simplon Orient Express), pitched to a luxury market rather than strictly a transportation service. They’re right, of course – the Orient Express has seen many iterations over the years, many of them completely unrelated to one another. But operational continuity or not, there’s something special about this train, and the name that has been synonymous with the romance of rail travel for well over a century.

The original Orient Express was launched in 1883, running once-weekly service between Paris and Istanbul (then still officially named Constantinople). The name is commonly assumed to refer to “The Orient“, a term which by the late 1800s had come to refer broadly to the whole “eastern world” of Asia. Yet the Orient Express has never crossed the Bosphorus into Asia itself. Reality is more mundane – the French “orient” is a synonym for “east”, and is derived from the Latin word for “rising” (ie, of the sun – in the east). It is therefore a simple translation of “East Express”. The operator, the Wagons-Lits company, also ran a Nord Express to St. Petersburg, and a Sud Express to Lisbon; these three flagship trains were so-named because they linked Paris to the northern, eastern and southern extremities of Europe.

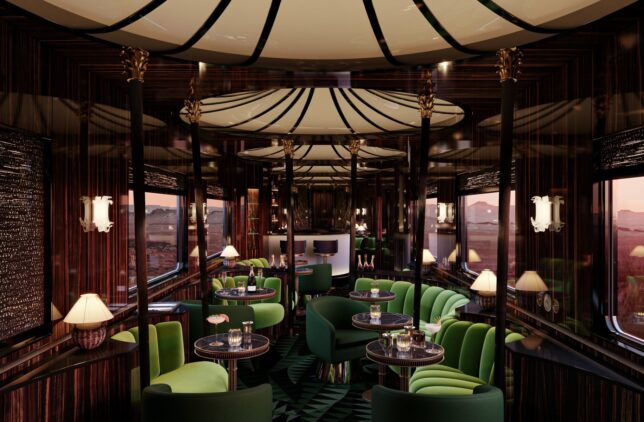

The Euronight Sleeper iteration of the Orient Express was discontinued in 2009, dubbed a victim of fast-trains and budget airlines. Just a decade later, in 2019 OBB’s NightJet reintroduced a Paris-Vienna service, though no longer branded “Orient Express”. Presumably, this is because OBB partner SCNF sold the branding to Accor Hotels in 2017. At time of writing, Accor have just revealed their plans for a grand reintroduction of the original Orient Express (along with the existing co-branded hotel chain) by 2025, with original carriages restored to an unprecedented level of opulence.

I’m not entirely convinced by the purists. The Orient Express may not share the unbroken operational lineage of the other trains on this list, but as a brand it is stronger than them all. If anything it has transcended mere marketing and entered the realm of global culture. One thing seems certain – a train bearing the name Orient Express is going to be with us for a long time yet.

1 – Flying Scotsman

The Flying Scotsman first ran in 1862 (then named the Special Scotch Express), which probably makes it the oldest train service still in operation anywhere in the world, and certainly the oldest that remains a major player in the transport mix. While only officially renamed in 1924, the express London-Edinburgh train had been popularly nicknamed the Flying Scotsman as early as the 1870s. With both the name and the service itself being a decade or more older than any other train still operating, the Flying Scotsman is a clear winner for the title “Oldest named-train in the world”.

It’s difficult to overstate the impact the railways were having on society at this time. Just a few decades earlier, the fastest stage coaches could do the London-Edinburgh journey in about two days, but more typically it would take a week or more. Upon its introduction to the East Coast Main Line in 1862, the Special Scotch Express covered the 632 kilometres between London Kings Cross and Edinburgh in 10.5 hours, with a single half-hour stop at York for coal and water. By the 1880s, competition with the West Coast Main Line led to a series of unofficial “races to the north“. In response to a high-profile derailment in 1896, the competing railways adopted a minimum journey time to Glasgow or Edinburgh of 8 hours, an arrangement that persisted until the early 1930s.

Nowadays, Class 801 Azuma rolling stock allows the the Flying Scotsman to cover the same distance in exactly 4 hours (158km/h average) with a top speed of 201km/h , making it the only train on this list to have evolved to a true “high-speed rail” service.

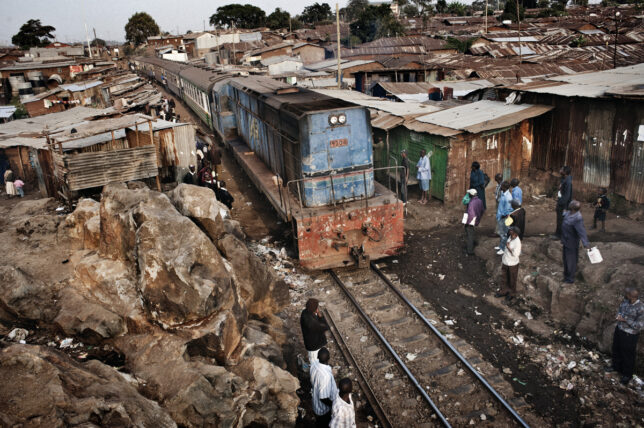

Honourable Mention – The Lunatic Express

Officially known as the Uganda Railway, this 1,060 kilometre metre-gauge railway was built in what was then British East Africa (modern Kenya) from 1896 to 1901, and ran from Mombasa to Kisumu on the shores of Lake Victoria. The ambitious project was first described as the “lunatic line” during fiery debates in the British parliament shortly after funding commenced, and the ongoing debacle of construction ensured the name became quickly entrenched, though never officially adopted. The vast colonial undertaking was hampered by tropical diseases, crippling heat, dust storms, steep chasms, vast swamps, hostile tribes, and most notoriously, a ten-month long attack on the Tsavo River Bridge construction camp by a pair of “man-eating lions“. Of the estimated 30,000 mostly Indian workers who worked on the railway during its five years of construction, over 2,500 lost their lives. Opinion was divided on whether the railway’s huge financial and human cost was worthwhile; some decried it as a “gigantic folly”, while others (notably Winston Churchill) hailed it as the epitome of British “muddling through”.

The railway was originally a fine service epitomising the romance of rail travel, catering to British colonists and bureaucrats travelling from the torrid equatorial coast to the cooler highlands, as well as well-heeled adventurers setting out on safari (notably former US President Theodore Roosevelt’s African Expedition of 1909). In its later years however, mismanagement and lack of maintenance had left the train outdated and uncompetitive. Deterioration of the track led to the discontinuance of the service west of Nairobi in 2012; the remaining 530km journey from Nairobi to Mombasa was then scheduled at 12 hours, but delays were expected; the train would commonly run anything from 3 to 24 hours late. Such an unreliable service was typically patronised by a mix of adventurous Western tourists and “cash-poor, time-rich” locals.

It was superseded in 2017 by the “Madaraka Express”, a new standard gauge “high speed” (120km/h) railway between Mombasa and Nairobi, funded by China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Running roughly parallel to the old line, it reliably does the run in 4.5 hours, about four times faster than its predecessor (on a good day). It is already planned to be extended to Kisumu and eventually to Uganda and beyond. It is in fact a very good example of railway modernisation to usefully competitive standards, without the astronomical expense of true “high-speed rail”. But the similarly imperial motive for the new line is not lost on observers.

The Adelaide to Melbourne Overland has just two very slow, return services a week. It commences its steep climb up the Adelaide Hills a street away from us and needs every horsepower of its two locomotives. There are also several mile long freight trains on the same line daily and have three or four locos. These drown out the TV on summer nights when our windows are open.